Introduction

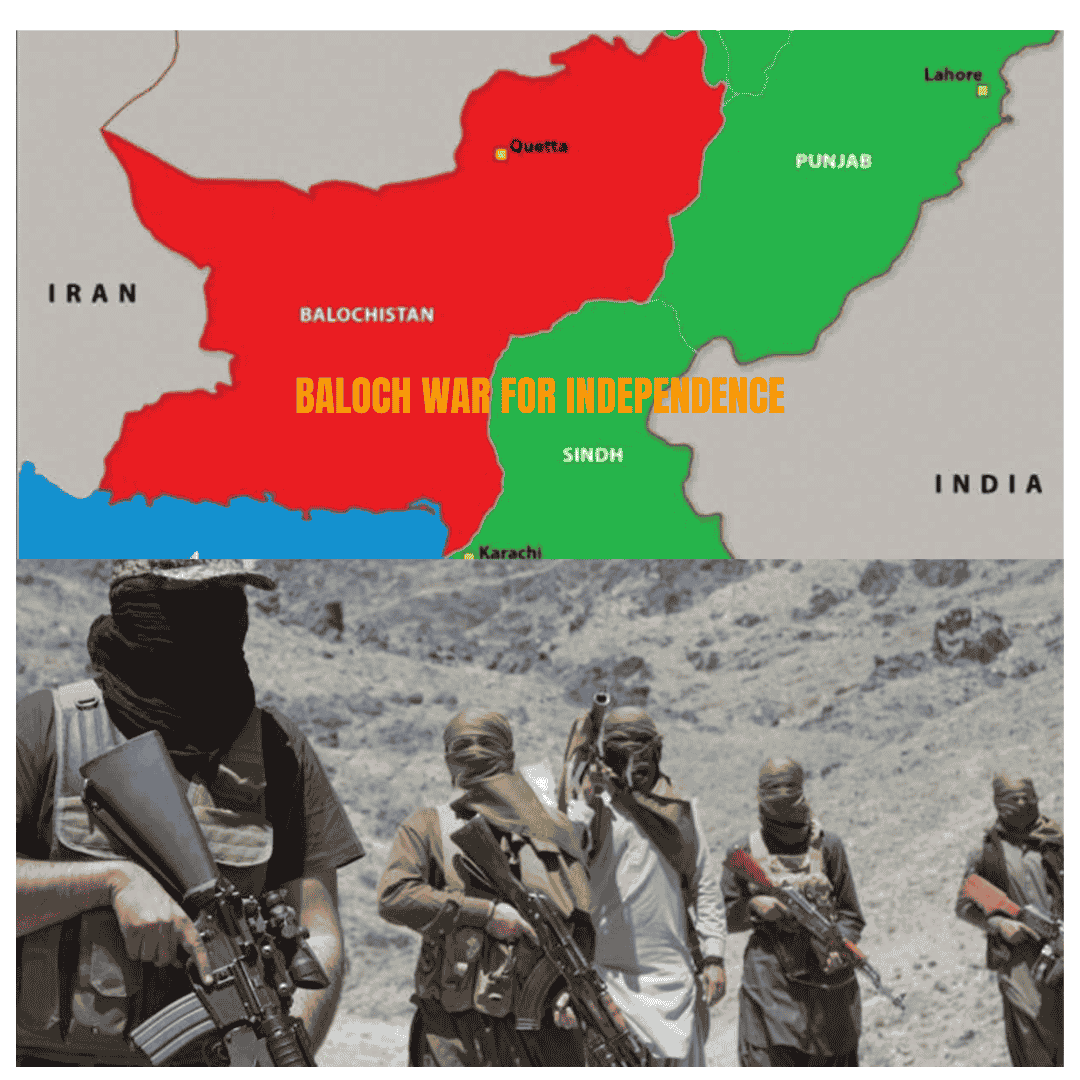

The Pak–Baloch conflict stands as a long-running, deep-rooted struggle that continues to challenge the internal cohesion and strategic outlook of the Pakistani state. At its core, the conflict is driven by competing narratives of nationalism, identity, autonomy, and control over natural resources. For decades, the Baloch people, an ethnic group with a distinct cultural, linguistic, and historical identity have accused successive Pakistani governments of systematic marginalization, political exclusion, and economic exploitation. These grievances have periodically sparked armed insurgencies, each more intense and enduring than the last.

Balochistan’s geopolitical significance cannot be overstated. The province occupies nearly 44% of Pakistan’s landmass and is home to vast reserves of natural gas, coal, copper, and gold. More recently, its coastal town of Gwadar has emerged as the centerpiece of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship component of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. While the Pakistani state views these megaprojects as tools of national development and strategic leverage, many within Balochistan perceive them as further encroachments on their land and resources, fueling a cycle of unrest and resistance.

Since the resurgence of the insurgency in the early 2000s, militant attacks against state institutions, infrastructure, and foreign interests, especially Chinese nationals have increased in scale and sophistication. In response, Pakistan’s military and intelligence apparatus have pursued an aggressive counterinsurgency campaign marked by widespread security operations, enforced disappearances, and allegations of human rights violations. Civil society groups and international observers have repeatedly expressed concern over the heavy-handed approach, which critics argue exacerbates alienation rather than fostering reconciliation.

Historical Background

The origins of the Balochistan conflict are deeply rooted in the contentious and often overlooked history of Balochistan’s integration into the Pakistani state. Before 1947, Balochistan was a mosaic of British-administered territories and princely states, the most prominent of which was the Khanate of Kalat. Although Kalat maintained a degree of autonomy under British colonial rule, it was never fully absorbed into British India. When the British departed, the Khan of Kalat initially opted for independence, asserting that Kalat had treaty-based sovereignty that entitled it to remain separate.

However, Pakistan’s founding leadership viewed Balochistan’s integration as essential to the territorial and strategic coherence of the new state. After protracted negotiations and increasing pressure from Islamabad, including military maneuvering, the Khan of Kalat signed the instrument of accession in March 1948, an act still regarded by many Baloch nationalists as coerced and illegitimate. The decision triggered the first of several Baloch uprisings, led by Prince Abdul Karim, the Khan’s brother, who took up arms in protest. Though this initial insurgency was short-lived, it set the tone for decades of recurring conflict.

Subsequent years saw growing frustration among the Balochs over their marginalization in Pakistan’s political and administrative structures. The federal government’s approach often prioritized central control and resource extraction over regional autonomy and inclusive governance. The second major insurgency erupted in 1958 following the imposition of martial law and the arrest of the Khan of Kalat. This pattern repeated in the 1960s, but it was the 1973–1977 conflict that became the most militarized and transformative episode in the region’s history.

The 1973 insurgency began when Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s government dismissed the elected Balochistan provincial government on charges of conspiracy and alleged links with Iraq. The crackdown prompted a widespread rebellion involving thousands of Baloch fighters, supported by some military officers who had defected. The Pakistani state responded with overwhelming force, deploying over 80,000 troops and relying heavily on air power and artillery. Thousands were killed, and the province remained under virtual military occupation for years. Despite eventually quelling the rebellion, the government failed to win over the local population or address the root causes of unrest.

In the following decades, Islamabad intermittently attempted to integrate Balochistan through development projects and political accommodations. However, these efforts were often undermined by continued military surveillance, lack of genuine autonomy, and growing disparities between the province’s resource wealth and the dire socio-economic conditions of its people.

The modern phase of the conflict, which reignited in 2004, is a continuation and an evolution of the historical struggle. It has been marked by the emergence of new actors, including secular nationalist groups like the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), and a more organized push for secession rather than mere autonomy. Unlike earlier revolts, this wave has sustained attacks on key economic and strategic targets, including gas pipelines, railway lines, and Chinese interests under CPEC. Simultaneously, enforced disappearances, targeted killings of intellectuals and activists, and a sharp rise in human rights abuses have contributed to a growing sense of siege among the Baloch population.

Ethnic, Cultural, and Political Identity

At the heart of the Pakistan – Balochistan conflict lies a struggle over identity: ethnic, cultural, and political. The Baloch people, an ethnolinguistic group with historical roots that predate the formation of modern nation-states, possess a strong sense of distinctiveness grounded in a shared language, tribal traditions, and a collective memory of autonomy under the Khanate of Kalat. This unique identity has long clashed with the post-colonial project of centralized state-building in Pakistan, which, since independence, has often emphasized a homogenized national narrative centered around Islamic identity and Urdu language at the expense of regional and ethnic pluralism.

Culturally, the Baloch have retained a tribal social structure marked by deep loyalty to tribal leaders, which plays a central role in local governance and inter-community relations. The Balochi and Brahui languages are widely spoken across the province, yet they have historically been underrepresented in national education and media institutions, contributing to cultural erosion. Efforts to impose a singular national identity have been perceived by many Balochs as attempts to marginalize or erase their heritage, reinforcing the desire for greater autonomy or independence.

Politically, the Baloch nationalist movement has evolved through several phases, from calls for provincial rights and cultural recognition to more assertive demands for self-rule and sovereignty. Various political parties and organizations, such as the Balochistan National Party (BNP), have advocated for non-violent political solutions within the framework of the Pakistani federation. However, a failure to secure meaningful concessions, coupled with repeated crackdowns on dissent, has pushed segments of the population towards militancy.

The situation is further complicated by the ethnic composition of Balochistan itself. While the Baloch remains the dominant ethnic group in many districts, the province is also home to Pashtuns, Hazaras, Sindhis, and Punjabis. In recent decades, state-led resettlement policies and demographic shifts have intensified Baloch’s fears of being turned into a minority within their province. These anxieties are not merely symbolic, they carry real implications for political representation, resource allocation, and cultural preservation.

Additionally, the region’s political alienation is reinforced by its economic marginalization. Despite accounting for the majority of Pakistan’s natural gas production and mineral exports, Balochistan remains Pakistan’s least developed province in terms of infrastructure, healthcare, literacy, and employment. This economic disparity, when viewed through the lens of cultural and political exclusion, deepens the perception among many Balochs that they are treated as colonial subjects rather than equal citizens.

Economic Exploitation and Resource Politics

One of the most enduring and deeply contentious dimensions of the Pakistan – Balochistan conflict is the perception and reality of economic exploitation. Rich in natural resources, Balochistan is often referred to as Pakistan’s “resource frontier.” It is home to vast reserves of natural gas, coal, copper, gold, and other valuable minerals. Yet despite this wealth, the province remains Pakistan’s most underdeveloped and impoverished region, feeding long-standing grievances of economic injustice and systemic neglect.

Since the 1950s, Balochistan has played a critical role in Pakistan’s energy matrix. The Sui gas field, discovered in 1952, became operational in 1955 and has since been a cornerstone of Pakistan’s energy infrastructure. While it has supplied energy to major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad for decades, large parts of Balochistan, including areas surrounding the gas fields have remained without basic utilities such as electricity and piped gas. This glaring asymmetry has reinforced the belief among Baloch communities that they are being used as mere providers of raw resources, with little benefit accruing to them in return.

Resource extraction in Balochistan has also been marked by opaque agreements, centralized control, and an absence of local participation. Major mining operations, such as the Saindak copper-gold project and the Reko Diq project, have long been at the center of controversy. These ventures have often involved foreign companies or federal agencies with minimal involvement from Baloch stakeholders. The lack of transparency in revenue-sharing mechanisms, limited employment opportunities for locals, and environmental degradation have fueled resentment and further alienated the local population.

Moreover, the advent of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has intensified these tensions. While CPEC is presented as a transformative initiative for Pakistan’s economy, many in Balochistan view it as an extension of extractive policies that exclude them from decision-making processes. The development of Gwadar Port, a linchpin of CPEC, is often cited as a prime example. Despite being located in Balochistan, the port’s infrastructure, economic zones, and associated projects are largely controlled by federal authorities and Chinese investors. Local communities have raised concerns over land acquisition, displacement, and the demographic impact of large-scale migration, fearing that the economic corridor will alter the province’s ethnic balance and cultural fabric.

The Pakistani state’s response to economic grievances has typically involved top-down development initiatives or security-led approaches rather than meaningful political dialogue or decentralization. While federal and provincial governments have announced special development packages, such as the “Balochistan Package” in 2009 and infrastructure investments under CPEC, these have largely failed to address the structural imbalances or restore trust among the Baloch people.

Role of Pakistan’s Security Establishment

Historically, the Pakistani military has viewed Baloch nationalism and calls for autonomy as existential threats to the territorial integrity of the state. This perception has led to a strategy of militarized governance in the province, characterized by sustained troop deployments, counterinsurgency operations, and widespread surveillance. The state’s response to successive Baloch uprisings—from the first rebellion in 1948 to the ongoing insurgency that reignited in 2004 has consistently relied on force rather than political dialogue.

The military’s presence in Balochistan is not limited to conventional operations. Intelligence agencies, particularly the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Military Intelligence (MI), have been deeply involved in managing the internal security landscape. These agencies have been accused by human rights groups and international observers of operating a parallel system of control involving enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and the intimidation of political activists, journalists, and students. According to reports by organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, thousands of individuals have allegedly been abducted over the past two decades, many of whom remain missing.

The security establishment’s dominance extends to the province’s political affairs as well. Baloch nationalist parties have frequently accused the military of manipulating elections, co-opting tribal leaders, and installing compliant provincial governments that lack legitimacy among the local population. This erosion of democratic space has left little room for meaningful political engagement, further driving disillusionment and radicalization among Baloch youth.

Economically, the military’s control over strategic development projects, such as the construction and operation of Gwadar Port and key nodes of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has reinforced perceptions of exploitation. These initiatives are often implemented under tight security, with limited consultation or benefit for local communities. The deployment of paramilitary forces, such as the Frontier Corps, to guard infrastructure projects underscores the securitized nature of development in Balochistan.

In addition, the military’s framing of the conflict through the lens of external interference, especially alleged support for Baloch militants from India and Afghanistan has often overshadowed legitimate internal grievances. While foreign involvement may be a factor, the overemphasis on external actors has allowed the state to deflect attention from domestic policy failures and justify the continued militarization of the province.

That said, the security establishment has occasionally signaled a willingness to pursue political solutions. Programs such as the Balochistan reconciliation efforts and amnesty schemes for insurgents have been launched intermittently. However, these initiatives have lacked consistency, transparency, and genuine local ownership, limiting their long-term impact.

Ultimately, the overreach of Pakistan’s security establishment in Balochistan has created a vicious cycle of repression and resistance. Without a fundamental shift toward a more inclusive and accountable model of governance, where civilian institutions are empowered, human rights are protected, and the political aspirations of the Baloch people are respected, the conflict is unlikely to be resolved.

CPEC and Geostrategic Calculations

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has dramatically altered the strategic landscape of Balochistan and, by extension, the broader South Asian region. Positioned as a transformative economic venture, CPEC is envisioned to connect China’s western Xinjiang region to the Arabian Sea via a network of highways, railways, energy pipelines, and industrial zones. At the heart of this vision lies Gwadar Port, located on the southwestern coast of Balochistan, which has emerged as both a symbol of strategic ambition and a flashpoint of local discontent.

From a geopolitical standpoint, CPEC offers China a shorter and more secure trade route for energy imports and exports, reducing its dependence on the Strait of Malacca. For Pakistan, the corridor promises to revitalize infrastructure, boost economic growth, and attract foreign investment. However, the realization of these strategic gains is inextricably linked to Balochistan, whose stability and cooperation are prerequisites for CPEC’s long-term viability.

Despite official narratives highlighting inclusive development, many in Balochistan view CPEC with skepticism and resentment. Many in Balochistan perceive CPEC as an externally imposed project, where strategic decisions are made without local input, and the socio-economic rewards are diverted to other provinces, deepening a long-standing sense of exclusion. There is widespread concern that the demographic influx linked to CPEC will marginalize the ethnic Baloch population in their province, eroding their cultural and political identity.

Security concerns surrounding CPEC have further complicated the situation. In response to repeated attacks on Chinese nationals and infrastructure most notably in Gwadar and along CPEC routes, Pakistan has deployed thousands of military and paramilitary personnel to secure the corridor. The creation of the Special Security Division (SSD) and naval expansions near Gwadar underscore the militarization of the region. While intended to protect strategic assets, such measures have deepened the sense of occupation among Baloch communities, reinforcing existing grievances.

Additionally, the strategic alignment between China and Pakistan via CPEC has drawn regional and international scrutiny. India has vocally opposed the project, particularly because it passes through Gilgit-Baltistan, a territory it claims as part of the erstwhile princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. From India’s perspective, CPEC represents not only a violation of sovereignty but also a deepening of China’s strategic foothold in South Asia. Moreover, there are growing concerns among Western policymakers regarding the long-term implications of Chinese infrastructure financing and the potential for strategic leverage over recipient states like Pakistan.

Regional and International Dimensions

The Baloch conflict, while deeply rooted in domestic grievances, has gradually assumed regional and international dimensions due to its intersection with great power rivalries, economic corridors, and evolving security alliances. The geopolitical location of Balochistan, bordering Iran and Afghanistan, and overlooking the Arabian Sea adds strategic weight to the conflict, transforming it from a localized insurgency into a matter of regional significance.

India-Pakistan Rivalry and Allegations of External Interference

Pakistan has consistently accused India of supporting Baloch separatist elements through intelligence and financial networks, particularly from Afghan soil. Islamabad points to statements from Indian officials referencing human rights violations in Balochistan as evidence of New Delhi’s alleged interference. India, on the other hand, has denied involvement in insurgent activities but has increasingly raised the Baloch issue in international forums, especially in response to Pakistan’s rhetoric on Kashmir. This tit-for-tat diplomacy has heightened bilateral tensions and internationalized the Baloch question in South Asia’s volatile security narrative.

China’s Strategic Stakes in Balochistan

China’s deep economic and strategic engagement in Balochistan, especially through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), has significantly altered the regional calculus. The development of Gwadar Port and allied infrastructure projects have made Balochistan central to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, persistent attacks on Chinese personnel and CPEC-linked assets by Baloch insurgent groups have raised concerns in Beijing regarding the security of its investments. As a result, China has increased pressure on Pakistan to neutralize the insurgency, while also exploring options such as enhanced intelligence cooperation and the deployment of private security contractors.

Afghanistan’s Role and the Post-2021 Landscape

The porous Pakistan-Afghanistan border, particularly in Balochistan’s north, has historically served as a conduit for insurgent movements, smuggling, and refugee flows. With the Taliban’s return to power in Kabul in 2021, Islamabad hoped for greater cooperation in curbing anti-Pakistan groups operating from Afghan territory. However, the evolving security dynamics remain fluid, with elements of the Baloch insurgency reportedly finding refuge or logistical support across the border. Moreover, the Taliban’s complex relationship with Pakistan continues to create uncertainty in cross-border counterinsurgency coordination.

Western Governments and Human Rights Advocacy

While Western governments have generally avoided direct involvement in the Baloch conflict, there is growing awareness of the humanitarian and human rights dimensions. Human rights organizations, think tanks and diaspora networks have highlighted cases of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and media blackouts in Balochistan. Although such reports have yet to translate into substantial diplomatic pressure, they contribute to an emerging narrative that could shape future international discourse on Pakistan’s internal security policies.

Current Situation in Balochistan

Wave of Enforced Disappearances

A disturbing escalation in abductions and enforced disappearances has gripped Pakistan’s Balochistan province, with fresh reports emerging of civilians, including minors being forcibly taken by security forces. Human rights organizations have raised the alarm, accusing the Pakistani military and its intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), of gross violations of international human rights standards.

According to reports by The Balochistan Post, on the morning of March 16, 2025, dozens of individuals were abducted near SBK University in the Nushki district. The Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), a prominent human rights group, has so far verified the identities of 11 missing individuals, including three minors. Those abducted reportedly include students, drivers, laborers, and residents. The Committee warns that the actual number of disappearances could be significantly higher.

“Many more people are missing,” Baloch Yakjehti Committee stated in a public appeal, expressing deep concern over the atmosphere of fear and distress spreading across local communities. Families of the disappeared continue to await news amid a climate of silence and intimidation.

The surge in disappearances is part of a broader pattern of state repression in Balochistan. In recent months, 2025 has witnessed a sharp increase not only in abductions but also in reports of extrajudicial killings. Human rights groups, both domestic and international, have repeatedly urged Pakistani authorities to cease these practices and ensure accountability, but the violations reportedly continue unabated.

The Baloch Yakjehti Committee has emphasized that the targeting of innocent civilians and minors constitutes a severe breach of human rights obligations and has called for urgent international intervention. “The silence of the international community emboldens the perpetrators,” the group said.

Balochistan, which was incorporated into Pakistan in 1948 following what many local groups describe as a “forceful occupation,” has long been a region of unrest. Political movements and armed groups have conflicted with the state, demanding greater autonomy or outright independence. Amid this decades-long struggle, civilians often find themselves caught in the crossfire of military crackdowns and insurgent activities.

Baloch Separatists Hijack Train in Daring Operation

In a dramatic escalation of the long-running insurgency in Balochistan, members of the banned Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) hijacked a passenger train on 11th March, 2025, carrying over 450 people, including civilians and security personnel. The incident, which occurred near Tunnel No. 8 along a mountainous railway route, has triggered a nationwide security alert in Pakistan.

According to Geo News, the attackers blew up a section of the track to force the train to halt inside the tunnel before opening fire on the engine. The train driver sustained injuries during the attack. Although security personnel aboard the train returned fire, they were unable to repel the heavily armed militants, who swiftly seized control of the train.

Unnamed sources quoted by local media suggest that 214 Pakistani personnel, comprising military, paramilitary, police, and intelligence forces are being held captive. The fate of the civilians on board remains unclear, with fears that hundreds may be under hostage.

A statement allegedly released by the BLA issued a chilling ultimatum: unless their demands are met within a specific timeframe, and if any military operation is launched, they would “destroy all prisoners of war” and demolish the train. The group’s message underscores a dangerous new phase in the insurgency, marked by bolder, more organized, and symbolic operations.

With 17 tunnels in the region and the train’s reduced speed due to rugged terrain, the attackers exploited both geography and weak communications infrastructure, authorities have been unable to contact the train crew due to a lack of mobile and telephone connectivity.

Balochistan government spokesperson Shahid Rind confirmed that emergency measures have been activated, and all local institutions are being mobilized to respond to the crisis. Intelligence and security agencies are closely monitoring the situation as it unfolds.

The Baloch Liberation Army, one of the most potent separatist groups operating in Pakistan’s restive southwest, has significantly intensified its activities in recent months. Its shift in tactics moving from sporadic ambushes to complex operations like this hijacking reflects a deepening insurgency and growing sophistication in asymmetric warfare.

As Pakistan confronts yet another internal security crisis, the incident also casts a renewed spotlight on the enduring grievances and volatility in Balochistan, a region marked by decades of economic neglect, ethnic tension, and calls for autonomy.

Arrest of Baloch Activist Dr. Mahrang Baloch

In a move that has drawn national and international condemnation, Pakistani authorities arrested renowned Baloch leader and human rights activist Dr. Mahrang Baloch on March 22, 2025, during a peaceful demonstration in Quetta. The arrest took place while she was leading a sit-in demanding justice for victims of enforced disappearances in Balochistan – a cause she has championed for years with unwavering courage.

Dr. Mahrang Baloch, a medical doctor and a prominent voice in Balochistan’s civil resistance movement, has become a symbol of peaceful defiance against state oppression. Her arrest came amid escalating crackdowns by Pakistan’s security forces on Baloch activists, students, and families of the disappeared.

Eyewitnesses report that security personnel in plain clothes and uniform swooped in during the protest and forcibly detained Dr. Baloch without a warrant or explanation. Several other activists and student leaders were reportedly taken into custody alongside her.

Human rights organizations, including the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), Amnesty International, and the Baloch Yakjehti Committee, swiftly condemned the arrest, calling it a blatant attempt to silence dissent and criminalize peaceful activism. Social media platforms erupted with the hashtag #FreeMahrangBaloch, as thousands of supporters abroad demanded her immediate release.

Dr. Baloch has been at the forefront of highlighting the systemic marginalization of the Baloch people, particularly the plight of families whose loved ones have been abducted often allegedly by Pakistan’s security forces. Her leadership during the recent long march for justice had drawn national attention and inspired a new generation of peaceful resistance in Balochistan.

As of now, Pakistani authorities have not released a formal statement detailing the charges against her. Her legal team and supporters say the arrest is not only politically motivated but also part of a broader campaign to suppress Baloch voices seeking truth and accountability.

The arrest of Dr. Mahrang Baloch may prove to be a watershed moment in Pakistan’s handling of the Baloch conflict, a conflict increasingly marked by repression, resistance, and rising calls for justice.